In September 2014, I started a three-month artist in residency at Brooke House, an independent sixth form college in my hometown of Market Harborough. I had recently moved out of London after several years and was temporarily living in the Leicestershire countryside after a family misfortune and pending a move to South Africa. The idea of being an artist in residence in the place where I grew up seemed bizarre to me, since the nature of my practice requires me to travel, but also an interesting challenge.

My practice is based around human understanding and interpretation of the animal kingdom. I examine how, throughout history, humans have responded to certain animals, and how these responses become intertwined in different cultures. It is the variety in our perception and logic that is formed from experiencing these animals that drives my practice.

The last couple of projects I had done had been in tropical rainforests and fauna-rich parts of the southern hemisphere. In England, I realised that my choice of animals to investigate might not be so diverse and abundant with the winter drawing in. I find that growing up in an area tends to make people take the surrounding fauna for granted, and this could be the case for me. I needed fresh eyes to look at what I had around that was accessible and also worth exploring.

Following on from a project investigating animal-related taboos in Madagascar, I was looking for animals with strange superstitions attached to them. The Madagascar project resulted in a book, ‘Creature Fady’, that, alongside examining various taboos attached to animals, focused mainly on the aye-aye (Daubentonia madagascariensis), a type of lemur. The aye-aye is so feared and linked to ‘the devil’ in Malagasy culture that it is often killed on sight by some inhabitants. I was looking to carry my research on from this area and I soon found one particular British creature that was surrounded by centuries of superstition and perceived in a similar manner. The Eurasian Magpie (Pica pica).

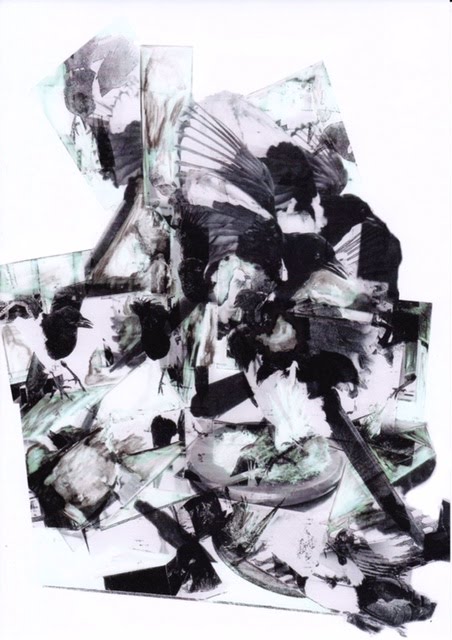

I was staying on my parents’ small, old, hobby farm and the magpies there were plentiful. Seemingly competing with – yet also in alliance with – their corvid cousin, the crow, magpies tend to dominate the surrounding sky and landscape. They mate for life and live and move around in pairs. But, on the farm, these birds were also packing together at times and there was a group of magpies of up to eight birds working as a team. This murder of magpies frequently fed on scraps from the farm and so were clearly ornithological ‘top dogs’ and not in any rush to move on.

Magpie numbers are said to have tripled in the past thirty years, owing to an increase in carrion prey in the form of roadkill. This goes hand in hand with an increasing human population and more cars on the roads. Magpies are also said to live and hunt in areas ranging up to twenty acres in radius.

Agile, hardy and regarded as one of the most intelligent birds in the world, the magpie flourishes from Europe over to the far east coasts of Asia, extending south to the northern coasts of Africa and west to the northern states of America and Canada. Its diet normally consists of insects, grain, and berries but also other bird’s eggs and nestlings. Hence, it is often unpopular with people who like garden birds to occupy their gardens. A few people, who are clearly not superstitious, will trap or shoot and kill these birds but most tolerate the infamous magpie.

So I chose to investigate why, apart from being a dominant presence in our skies, does the magpie seem to capture such a degree of our attention? Why is this particular bird so significant in British and worldwide folklore?