Florence Trust, Islington, London

15–29 August 2025

Drawings in the Depths is an illustrated journey that visually explores the pilgrimages our ancient ancestors made to create artworks in sacred spiritual spaces across Europe during the last Ice Age.

As an artist whose practice typically focuses on human understandings of the animal kingdom, this body of work marks a branching path from my usual research. Yet it’s one I’ve long wanted to explore since I started visiting these prehistoric sites. Each time I visit these incredible underworlds and witness the marks left many thousands of years ago, I am captivated by imagining the experiences of those early people, venturing into dark, alien spaces to create images that still resonate today.

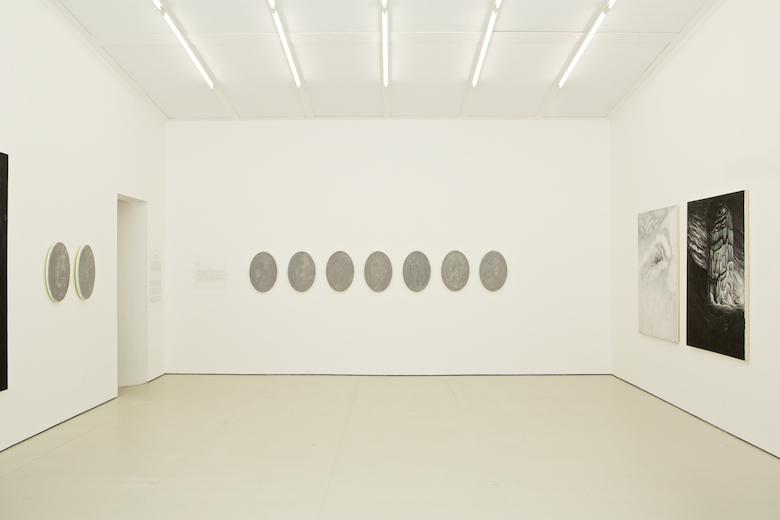

Pilgrims, 2025.

The drawings, scored into concrete on wooden boards, are based on some of the earliest human portraits, etched into limestone over 15,000 years ago and discovered in the Le Marche cave in France in 1937. This cave is thought to have been a meeting place, possibly even a trading hub.

The figures depicted were nomadic, migrating across Europe with the seasons in search of fair weather and food. To survive the brutal Ice Age winters, they likely set up camp at the entrances of vast cave systems in the mountains, where temperatures remained stable and offered some protection.

Only a few would have dared to go deep into the caves. These were pitch black, dangerous places, home to hibernating bears and lions, disorienting and complex. The decision to take a torch and drawing media far into these labyrinths would have been a profound and risky one.

The images discovered deep within these caves, sometimes more than a kilometre inside, have been interpreted as spiritual messages: prayers to animal gods or sorcerers, or rituals of transformation into other beings. Other drawings show animals with incredible anatomical accuracy, depicting the behaviour and relationships of the wildlife around them. Scenes of predator and prey are common, visual accounts of their lived environment, transcribed into the walls of these hidden galleries.

There are also depictions of fertility, including sexual organs, reminding us that people have not changed much, psychologically, over the millennia. But these were not casual scribbles on the back of a dirty van. They were made in inaccessible, highly private locations, suggesting the images were offerings or messages intended not for others in the tribe, but for something or someone else entirely.

Many signs and symbols remain undeciphered. Archaeologists continue to debate their meanings, but as with much of prehistory, interpretation often blends logic with informed speculation.

What we do know is that these early humans, too often dismissed as primitive ‘troglodytes’ were far more sophisticated in their image-making than previously believed. These drawings weren’t just born of hunger or survival. They were acts of reverence, celebration, connection. These people weren’t only recording the world, they were spiritually engaging with it, using drawing as a ritual to become closer to nature and something beyond being human.