Paradise Lost – a solo exhibition by Tom Van Herrewege at the KZNSA Gallery, Durban, South Africa. 21st May – 9th June 2013.

The title ‘Paradise Lost’ is ‘borrowed’ from the epic poem by English poet John Milton. The poem concerns the story of the fall of man, and of (our) expulsion from Paradise.

This new body of work by London-based artist Tom Van Herrewege draws the viewer inexorably, beguilingly, into the beauty of the animal kingdom…like a snare.

Van Herrewege was on a residency with the KZNSA Gallery as part of the Gallery’s Social Art in Development (SAID) Programme, supported by the National Lotteries Distribution Fund. The artist undertook a similar residency in Cairns, Australia in early 2011. He holds an MA in Fine Art and Painting from the Wimbledon School of Art, London (2005/6). The artist’s previous exhibition titles, ‘Collections’, ‘Are you Dead’, and ‘Transfauna’, provide a telling glimpse into his abiding interest in the animal kingdom – particularly the ways in which we as people (also animals, but I will get to that) collect, interpret and portray ‘our’…and here lies the rub…fauna. This new exhibition was produced over three months in Durban in the autumn of 2013.

Notes Van Herrewege, “My research is largely informed by the history of animal representation within art and natural history. I look at the ways animals are presented through the media and their display in collections and the various languages we invent and adopt to understand them. I am drawn to the abstraction of information that occurs through man’s translation and presentation of findings from natural history in museums, Wunderkammern and collections of curiosities.

“The allure of ‘the big 5’ drew me briefly to SA in 2002. But my main subject matter actually focuses more on the less celebrated creatures of the world such as insects, reptiles and other lesser known or admired fauna.” Most notably, as the artist expressed in casual conversation, “creepy-crawlies that can kill you…”

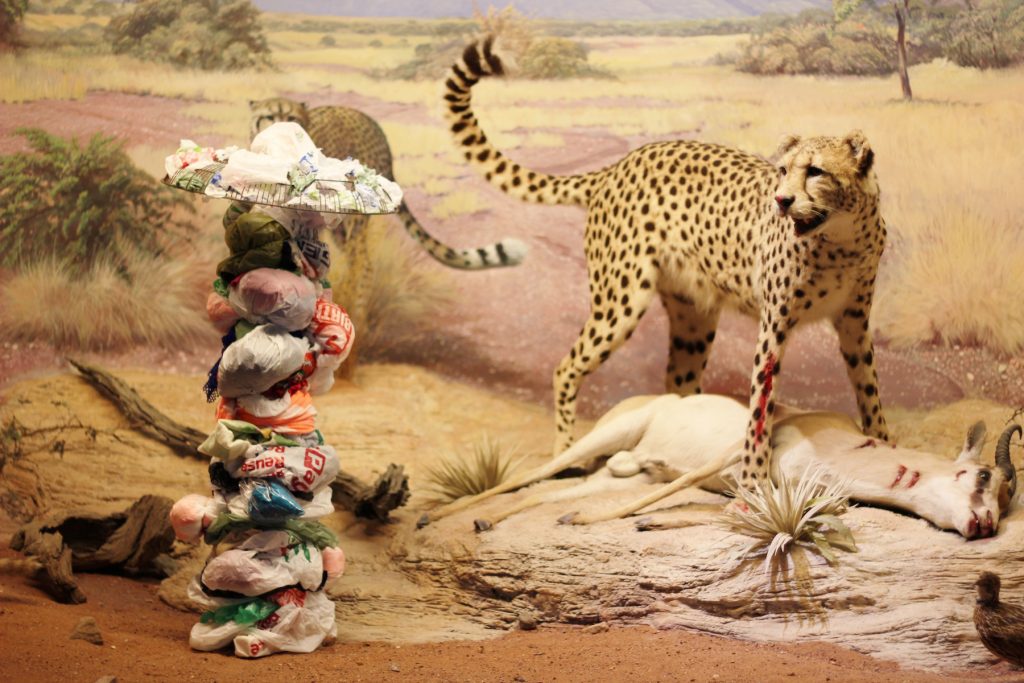

Tom’s interest in taxidermy (fraught as this art form is with a history replete with hunting and expropriating) lead him in Durban to investigate the dioramas at the Durban and Pietermaritzburg Natural Science Museums. This artist’s work often depicts features from animal forms, juxtaposed with man-made materials in order to highlight the beauty of the animal. With trepidation the artist approached these institutions with a view to placing his sculptures in the dioramas.

“It is the ways that animals are removed from their environments and understood as both objects and living beings that informs my artistic research and practise, within which no animals are ever harmed or killed for the purpose of making art. I choose to portray animals in my work through a great admiration for them. I re-examine these subjects using the animal’s physical form as an entry point for transformation into a different physical form – placed in a reconsidered locale. These reworked images act quite like my own solutions to the complexity of the animal forms.

In his ‘Diorama series’ of acrylics on canvas the artist treats the diorama diagrams as utopian colouring books. Without the text that conventionally accompanies each diagram they become mysterious and open to various interpretations, leaving one to wonder what is happening in the scene. He includes paint and colour as a human interference, mainly taking form as waste material that the animals are interacting with.

“What attracted me to these diagrams is the simple use of lines and shapes and the bare minimum of information as drawings. Also the numbering system can suggest a process of actions once the text is taken away from the diagrams.” It provides a telling testimony to the role of colonial collectors in the debasing of the dignity inherent to all creatures that these dioramas reflect.

Included in the ‘Diorama series’ are photographic prints depicting Van Herrewege’s sculptural works placed into these utopian scenes. The artist’s innovative use of often synthetic materials provides a foil to the natural beauty of the long-dead diorama inmates, and as such the juxtapositions acquire an alien, almost apocalyptic feel.

These works do not humanise, rather they speak to inhumanity.

They appear as assemblages of litter in a constructed natural environment (the dioramas) that may have been created out in the wild. And they are placed so the animals are encountering them in various different ways.

Protecting the object, attacking the object, investigating the object…the proverbial hunted hunting the hunter reveals itself as a powerful raison d’être in Van Herrewege’s work.

Stuffed bears can be dangerous…..the photographic installation views of the artists foray into the polar bear diorama at the Natal Museum necessitated the donning of an obligatory protective ‘space suit’ complete with gas mask. This because the polar bear in question is riddled with arsenic. The key to the durability of Victorian taxidermy lies with a recipe (as a preservative) known as ‘arsenical soap’, highly effective against insect attack, arsenic is also toxic to humans. Because of its toxicity the use of arsenic is now prohibited in the museum community.

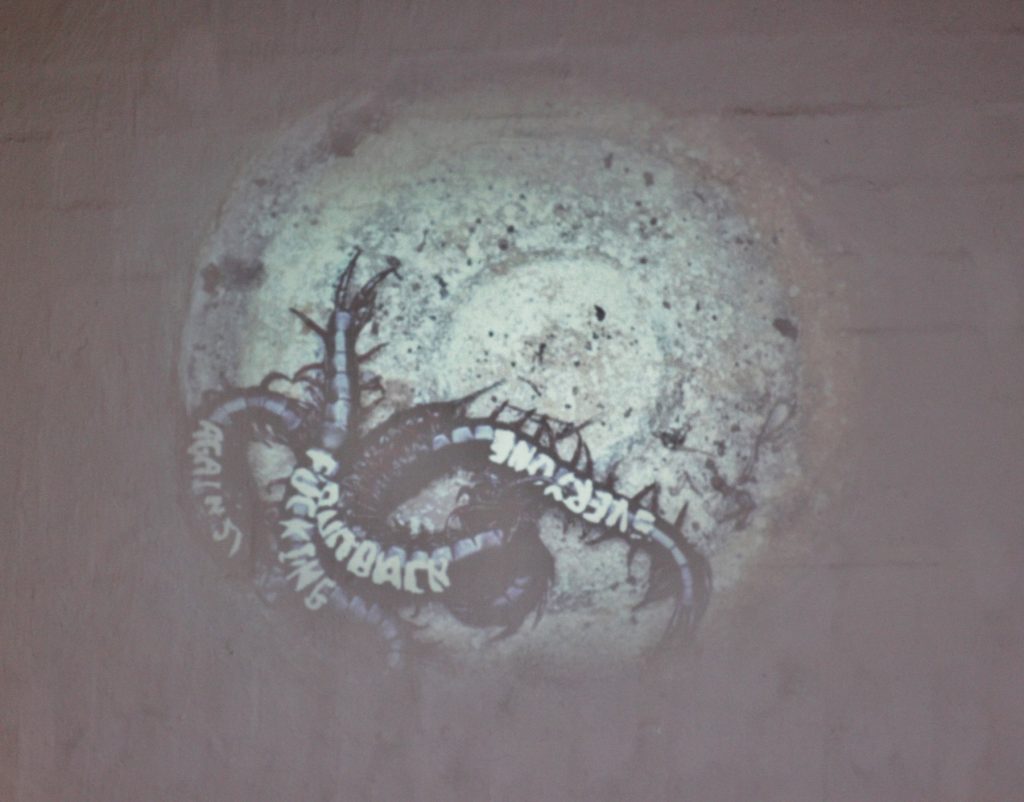

‘Everyone Against The Fucking Outback’ (Videography, 10 mins) is a chilling take on the phobias that we humans so commonly endure for venomous snakes and insects. Here the work suggests that these phobias extend to the cultural prejudices that the ‘civilised’ citizens of urbanity feel toward the uncivilised outback or ‘wilderness’.

The video presents the artist’s reaction to the segmented form of the Scolopendra centipedes (aka giant centipedes) that were common sightings when Van Herrewege spent a short time working on a sheep station in central Queensland. We South Africans typically kill them with a brick. (The crawlies here were safely returned to Burnam Bush and Pigeon Valley in Durban, from whence they came.) The text written on the segmented spines of the centipedes infer to a phrase the artist overheard in a bar, “Everyone against the fucking outback” Why is the notion of modern (human) city life so antithetical to the notion of the wild or ‘untamed’?

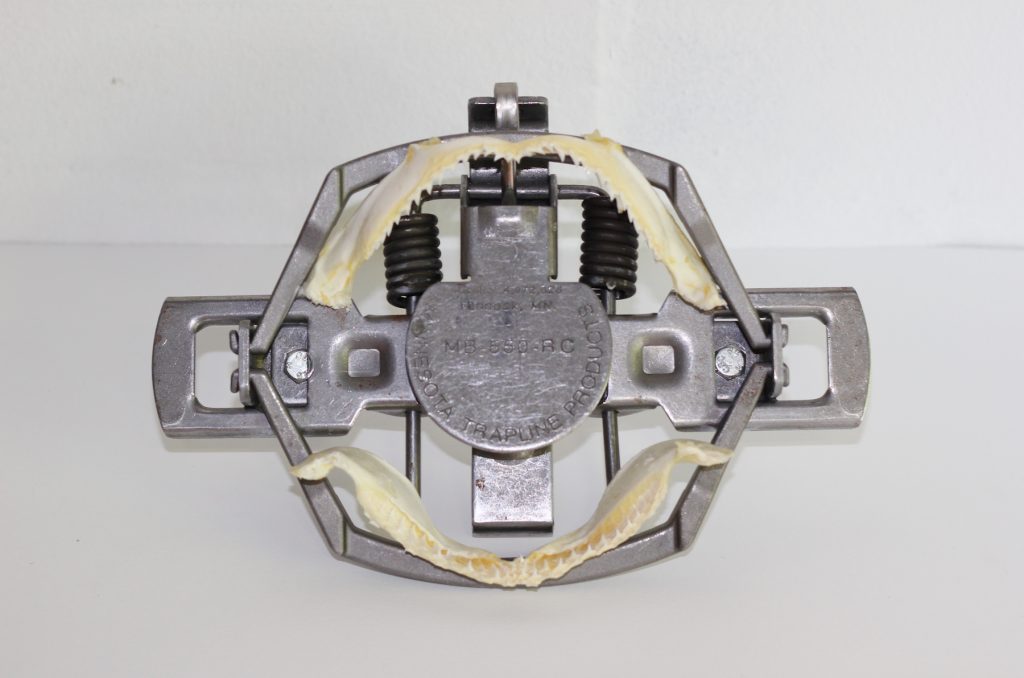

An extraordinary sculptural series presents four very real, very deadly steel spring ‘bear traps’, subverted by the artist to include the addition of equally real sharks jaws and teeth.

There is a videography work of a venomous snake resplendent and very much alive in a non-existent drawing of a box on the Gallery wall.

“I tried to break the spell of the wilderness, which held him in its grasp, reminding him of how he had satisfied his monstrous desires. I was convinced that his dark and secret feelings and instincts were what had brought him out to the jungle in the first place, where he could be beyond the rules of society. The terror I felt was not the fear of being killed, though I did feel that too…I tried to break the spell, the heavy, mute spell of the wilderness that seemed to draw him to its pitiless breast by the awakening of forgotten and brutal instincts.” Joseph Conrad, Heart of Darkness.

Whilst it seems that we may have been expelled from paradise, as the title of this exhibition suggests, our collective humanity is not quite out of the woods yet. A must see exhibition.

Bren Brophy

KZNSA Gallery Curator in conversation with Tom Van Herrewege

Durban

May 2013