Superstitious beasts is a body of work put together as part of my research into human- animal relationships, their associations and understandings across the world throughout history. It is the way in which different people culturally have understood particular species from the animal kingdom in certain ways that I question and explore within my work.

The works on display in the gallery at Loughborough University were a selected few I made between 2014 and 2016 and the focus is on animal related superstitions and their involvement in folklore. The works chosen were from research into this subject area in the UK, South Africa and Madagascar. These are the three places that so far I had researched, visited and managed to collate information on this often poorly recorded subject area.

I intend to continue developing this ongoing project by researching and visiting particular areas of interest across the globe. By doing this I can bring together a comparison and an analysis of cultural similarities and differences in people’s understandings of the animals we encounter and live around and also I can learn more about how the human mind works in this way.

Artworks in the exhibition.

An infinite rhyme, 2015. Mirrors, table, chair, taxidermied Magpie, books, easels, typewriter and paper. Dimensions variable.

Six mirrors mounted on easels face one another with a table and chair between them. On the table is a typewriter and a taxidermied magpie that is reflected as far as the human eye can register through the infinity effect. The viewer is invited to sit at the table and to encounter the magpie’s infinite reflections created between the six opposing mirrors. The viewer is invited to interact with the artwork by adding to the ongoing infinite rhyme being typed up before them. As long as the rhyme is added to by people interacting with the work, then it remains an ongoing development of the artwork.

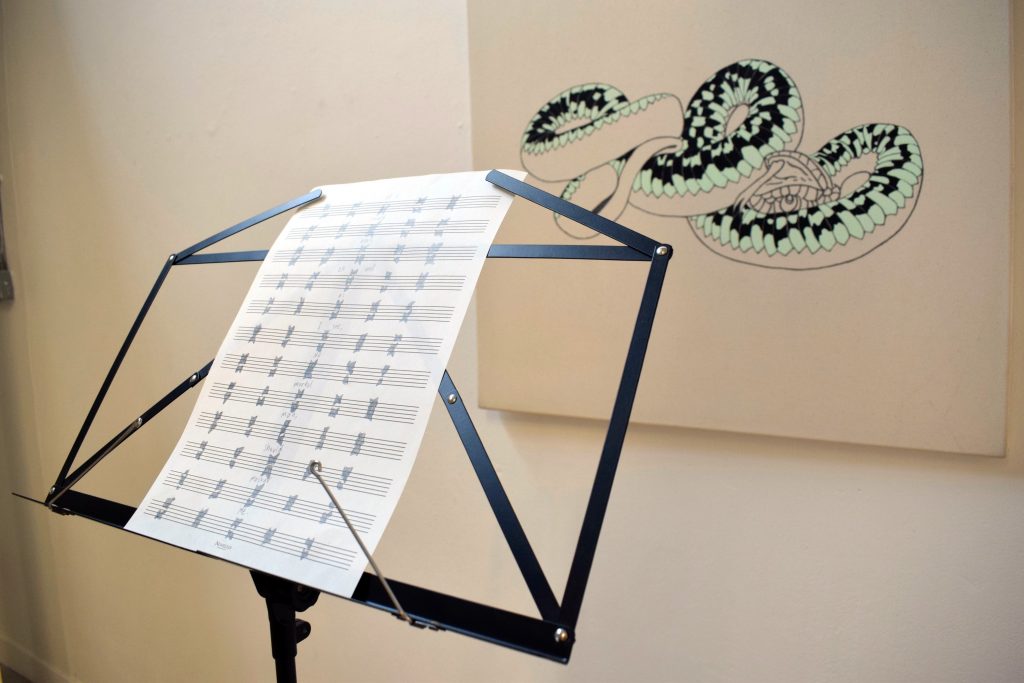

If I could hear as well as I see.., 2016. Oil paint and marker pen on canvas, graphite on paper on a music stand, recorded music. Dimensions variable.

In British folklore, the underbelly markings of the grass snake were said to have been a code or language that if translated would spell out the phrase ‘if I could hear as well as I see, no mortal man should master me’. It is a defensive tactic that when the snake is threatened it will roll over onto its back and feign death. When people would encounter this behaviour they would also be confronted with these strange markings.

I decided that I wanted to try and literally translate the markings from this particular specimen and so I copied the unique patterning onto a sheet of music paper whilst thinking about how this could be read as music somehow. I then asked a musician friend to attempt to make sense from this and to write a piece of music from the drawings. So the artwork is interpreted through different mediums moving from a photograph to a painting to a drawing and eventually into a piece of music.

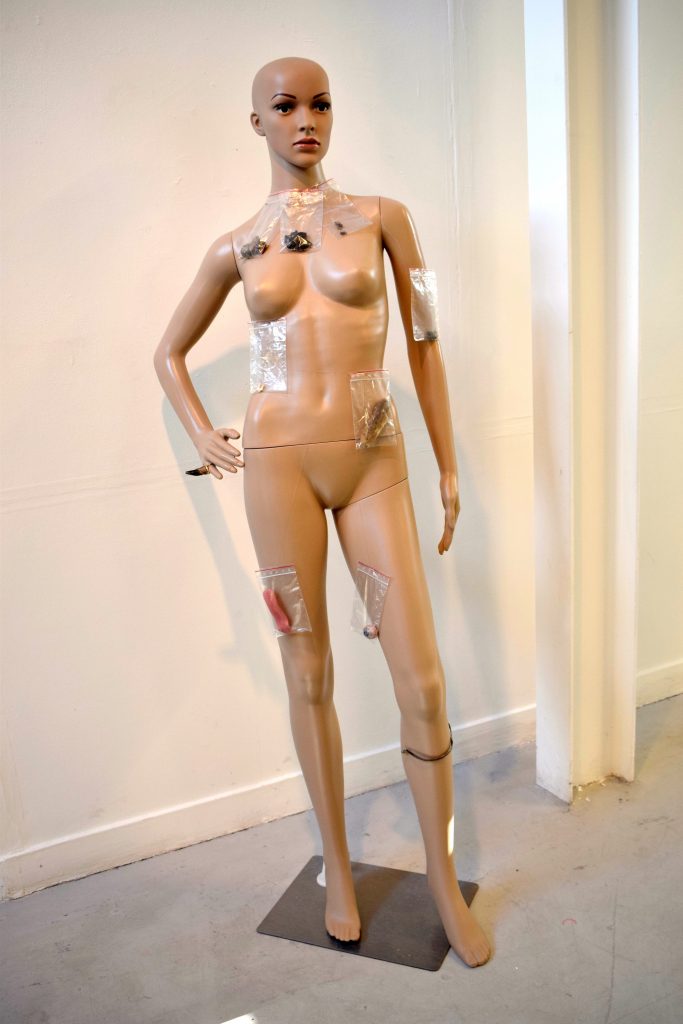

Untitled (hypochondriac), 2016. Mannequin, clear plastic bags and varying dead animal’s/animal parts. 170x40x35 cm’s.

The mannequin that is adorned with clear plastic bags containing animal parts is a sculptural illustration of how people once carried complete, or parts of, certain animals around with them.The specific animal was to be carried next to a particular area of the human body as a cure for varying problems with one’s health. What interests me with these old ideas in folklore is why specific species would be associated with curing illnesses in people and their logical links to human anatomy. By physically placing the actual animal’s/animal parts upon the mannequin I am trying to make sense of how these ideas were developed and to get an understanding of this logic.

Foundations for a retreat, 2016. Wood, metal tray, petroleum jelly and animal bones. 280x183x215 cm’s.

This wooden house like sculpture is built to show how certain animals would be/are incorporated into the home for varying spiritual reasons through folklore in both Britain and in Southern Africa.

Earlier in 2016 I visited South Africa and accompanied a guide through the Muthi markets of Durban to gather information on how animals are used in this traditional medicine and in Zulu folklore. I wanted to compare how these ideas are to those of British folklore.

The sculpture is made quite like the most basic start one could make of a building and with the animal parts being prioritised with importance in its initial construction. It is the foundations of what would eventually become a fully walled and secured building. A place to retreat to with these superstitious ideas people cling on to to protect themselves. The horse’s hoof in Zulu folklore should be placed above the door to absorb your nightmares. The tray contains Donkey fat which in Zulu folklore should be spread under the home to protect the place. The horse’s skull would be incorporated into the building of a house in British folklore to bring good luck and the cat skeleton is present as cats were also bricked into the walls alive to ward off evil spirits.

Fragile in its construction, the work also acts as a metaphor for the human mind and its paranoia’s and how we hold onto certain superstitious idiosyncrasies that can litter, distort and even destabilise it.

Medic, 2015. Black and white digital photograph. 37×59 cm’s.

In British folklore, the donkey has been understood as being holy, due to its involvement in the transportation of Mary and Jesus to the site of his birth. People believed that the Donkey possessed medicinal powers and so they would pass their children around the animal (usually circled around the animal’s midsection) and this would be repeated for the appropriate number of rotations depending on the illness that needed curing.

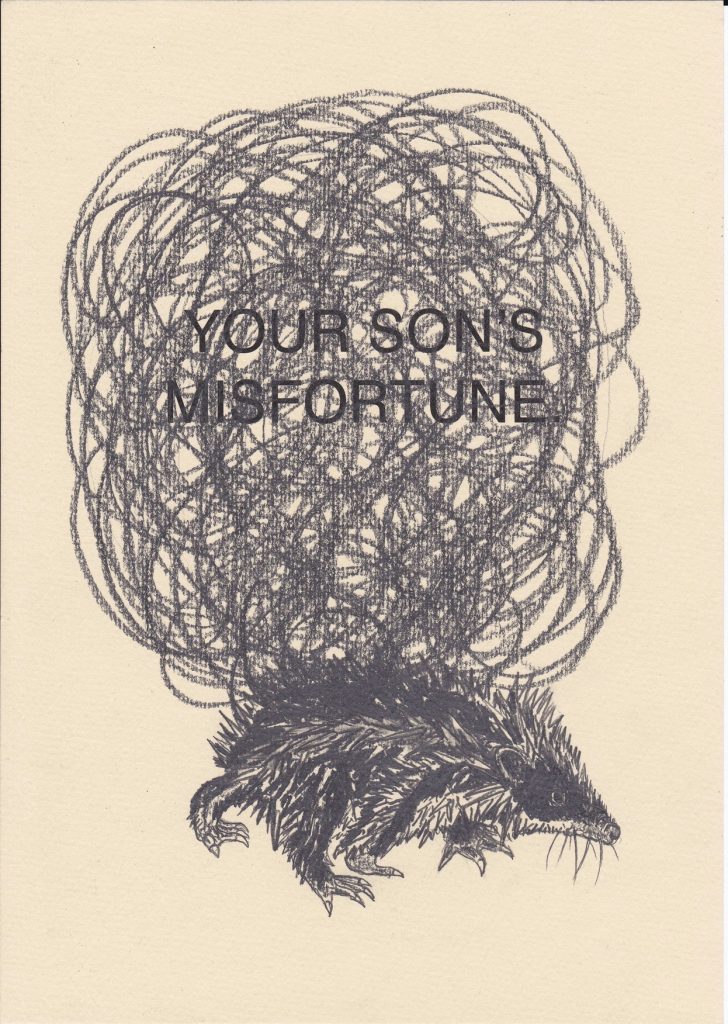

Your son’s misfortune, 2014. Graphite on cartridge paper. 29x21cm’s.

The animal that is drawn here carrying a load of scribbled mass upon its back is a called a Tenrec and they live in Madagascar. The Malagasy people have strong superstitions and there is much varying folklore (fady) from region to region based around the animal kingdom on this huge island.

In the South of the Island, local people believe that if a father wishes to rid his son of an illnesses, that cannot be cured by a doctor, then he must capture a large Tenrec. Then the Tenrec is to be taken to a sacred Baobab tree and tied to it with a piece of string. He must then pray to the tree for the safe recovery of his son and then untie and release the Tenrec. The animal is believed to then return to the undergrowth and out of sight, taking the negative problems of the boy with it.

What interested me about this fady was why this particular animal had earned this association in Malagasy folklore and whether it is to do with its spiny appearance. I am interested in the set of actions required here and the involvement of the Baobab tree with the idea of a transfer of energy from man to a tree and then to an animal.

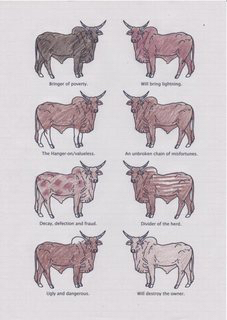

Death chart: Zebu, 2014. Colouring pencil on paper. 29×21 cm’s.

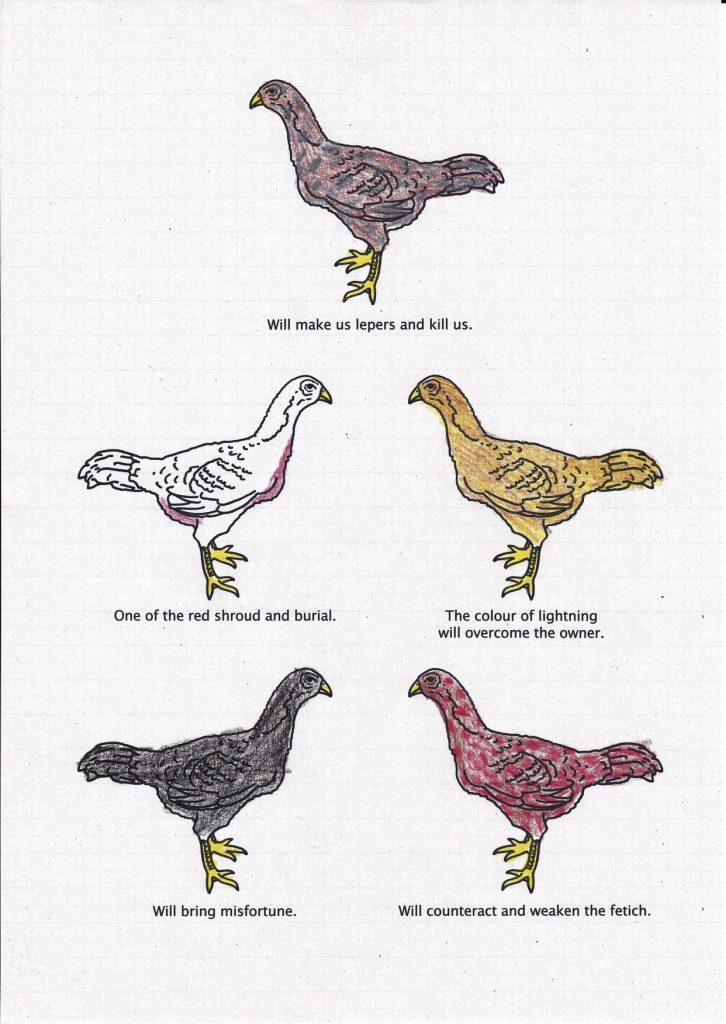

Death chart: Fowl, 2014.Colouring pencil on paper. 29×21 cm’s.

The cattle and fowl shown on these drawings are important livestock to the people of Madagascar and to the average Malagasy person they hold significant financial value. The animals have been coloured in here to show the particular colour variations of these cattle which are deemed unlucky in Malagasy superstitions with the reasoning written below each one. These animals would all be killed straight away if born with one of these colourations and this would be quite a severe loss to the owner. Despite the extreme poverty in Madagascar and need for food and money, superstitions (fady) are so closely held on to with often with higher importance than wealth.

Banded Mongoose, 2016. Graphite and ink on paper. 28×19.5 cm’s.

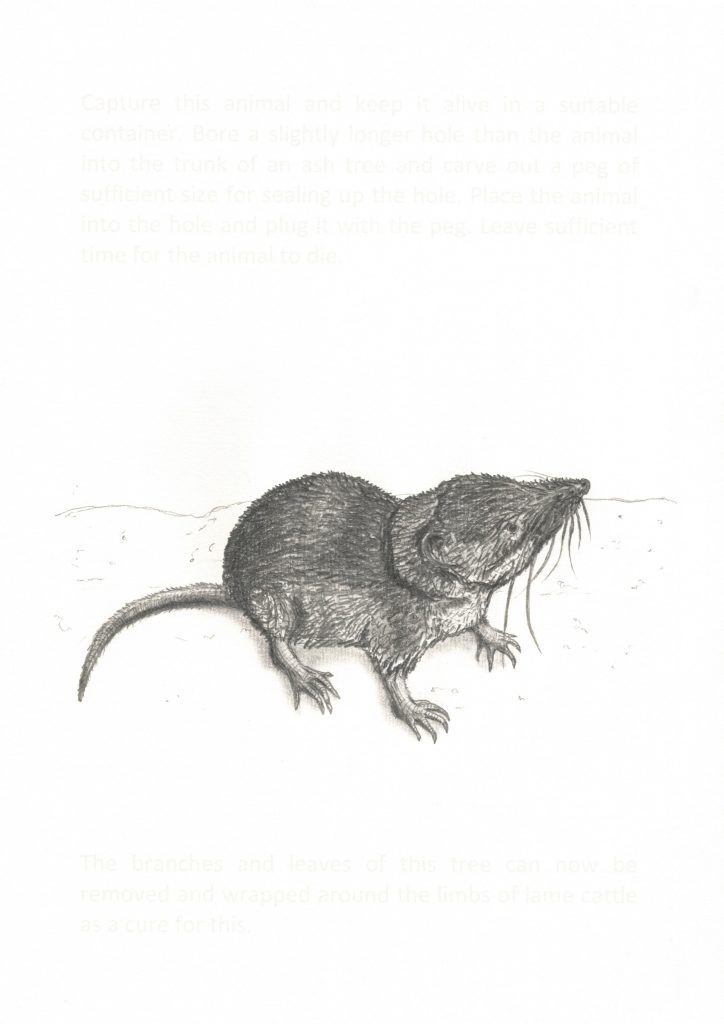

Eurasian Shrew, 2016. Graphite and ink on paper. 28×19.5 cm’s.

Vervet Monkey 2016. Graphite and ink on paper. 28×19.5 cm’s.

Eurasian Hedgehog, 2016. Graphite and ink on paper. 28×19.5 cm’s.

The four drawings of individual animals are chosen from folklore in the UK and from South Africa. These animals in folklore would be killed and then their body parts would be used or discarded in varying ways for different reasons. The reasons for this are printed very faintly above and below the drawing to work like subliminal texts that explain how people would use and look at these animals.